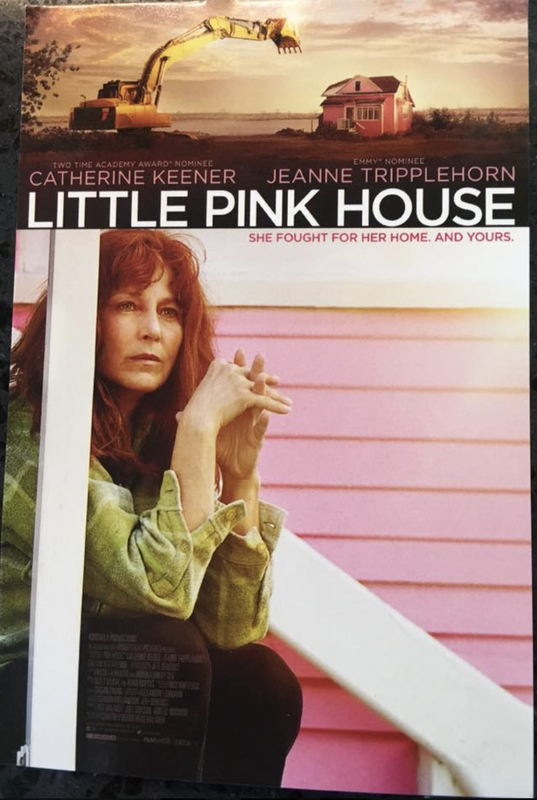

Little Pink House is an independent film that tells the story of what it dubbed "the most hated court decision." In the late 1990's the economically depressed city of New London, Connecticut, got the idea to "re-develop" a working class neighborhood to lure a big corporation to the city. Corporate giant Pfizer stepped into the role, and the political movers and shakers couldn't do enough to please them, including using eminent domain to demolish a community and hand it over for corporate use. It was a crisis for the community. And when crisis strikes, the community says... "someone should do something about this." Resident Suzette Kelo unwittingly became "someone," as most "someones" usually become; not voluntarily and not by design, but out of necessity. Becoming "someone" is not a conscious choice and the goal of becoming is never recognized until after it happens. All of a sudden, there "someone" is, thrust into a role on a path they never knew existed and aren't quite sure where it leads. But "someone" never quits and never looks back, and sometimes the path never ends, but winds on to things never imagined.

Kelo rallied her neighborhood (feel good moment) and fought the city every step of the way. The pinnacle of the neighborhood rallying was a "public meeting" put on by the city's cluelessly arrogant economic development woman. The "town hall" format soon went south, with sarcastic questions that began with Kelo and soon devolved into a free for all shouting match between the residents and the economic development woman. "This is bullshit!" Oh how many times have we all wanted to shout that out? (And maybe one time I actually witnessed it happen).

As Kelo's neighborhood begins to be torn down around her, help finally arrives with a pro bono lawyer from The Institute for Justice. Kelo becomes the sympathetic face of the community and is offered up to the media in order to build the public story. Like any ordinary person thrust into the spotlight, she's unsure of herself. The coaching she receives from IJ is classic. You are the expert on your own story -- simply tell your story and sidestep or defer the questions that fall outside your expertise. After a tentative start, Kelo eventually finds her confidence. And the court battles begin. There's a self-involved city lawyer who reminds me of a slightly less arrogant version of an attorney I met once upon a time, and a judge who's almost a dead ringer for a judge I also once met. I found these parallels personally stunning to the point of being a bit distracting from the story for me, but adding to the building feeling that I know these characters. I've met them hundreds of times over the past 10 years, although the faces and names change each time. Yes, it was just a movie last night, and these were but actors, but the actions and dialogue were a spot on portrayal of the very real stories that have happened time and again. The characterizations were authentic, without any of Hollywood's over the top exaggerations and heroic hogwash. Even the villains were real - mentally screwed up by their own egos and privilege to the point that they can do these things to other human beings without any conscience. That's because the villains don't see the people they affect as real -- they simply become numbers and statistics. A dot on a map. A name on a list. Someone to be bulldozed aside on the road to fame and fortune.

I'm sure you know that Kelo eventually lost her battle at the U.S. Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision. But in the wake of that decision, many states tightened up their laws to prevent eminent domain for the sole purpose of economic development. But where are we now, more than a decade later? Has the memory dimmed? There's still plenty of people being wiped out by the threat of eminent domain for private gain, where everyone's Little Pink House would pay more taxes if it was a Walmart... or a new electric transmission line promising to provide "cleaner" or "cheaper" electricity to communities far, far away.

The Institute for Justice, the hero fighting for the little guy in the film, has refused to involve itself in any eminent domain battles waged by utilities upon private property owners. As I understand it, they get a bit tangled up in the fact that utilities sometimes need eminent domain to provide service to those who don't have any, or to ensure utility service stays reliable. If that were the only reason utilities used eminent domain, perhaps they'd be justified.

But we've all become so used to the idea that utilities have the power of eminent domain that we've failed to notice the way they've managed to stretch that authority into situations that no longer fit the original purpose. Should a transmission company building for its own profit be able to decide where to ship power for economic or environmental purposes? Who gave utilities that kind of authority? When did someone's desire to use "cleaner" electricity become a good enough reason to take the property and effect the economic well-being of another person many hundreds of miles away? When does saving one geographic customer base a few cents on their electric bills become a just reason for taking from a land and business owner several states away?

It's time to take a look at a utility's reasons for eminent domain and keep it in check to make sure that it serves a true public use for everyone, and not just to serve the wants of a select group.

If you've ever been involved in transmission opposition, you need to go see this movie. It has absolutely nothing to do with electric transmission, but everything to do with opposition.

Find out where it may be playing in a theater somewhere near you here. And if you have to drive a bit to find it, it's worth it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed