Do we really need it?

Elected officials, including Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, Maryland General Assembly Delegates Szeliga and Reilly, Pennsylvania House representatives Kristin Phillips Hill and Stan Saylor, have all joined citizens of both states in calling for cancellation of the IEC project.

This project never was a good idea in the first place. It was PJM's first competitive market efficiency project, where PJM floated a congestion "problem" and eager transmission owners (and wannabe transmission owners) submitted ideas for solutions they could build if selected. PJM selected what it felt was the best idea, and four years later here we are. Four years. That's a long time in the energy world, where needs are constantly fluid. Generators going on and off line, transmission upgrades, and changing load constantly alter the need for new transmission. Attempting to make a changing market "more efficient" by adding new transmission, and then waiting more than six years to actually bring the new transmission online is an exercise in futility. It's nothing but a cash cow for the transmission company lucky enough to be guaranteed to recoup its investment (plus interest) in such an unnecessary pursuit. PJM's market efficiency competitive transmission process is deeply flawed and can probably never work. Transmission just takes too long, while the "congestion" proposed to be alleviated is a constantly changing and fleeting issue.

The PJM Market Monitor (MMU), Monitoring Analytics, issues yearly reports that cover congestion in the region, along with other issues to make a determination whether PJM's markets are competitive. The MMU's function is to monitor and report on PJM markets and make recommendations to keep markets competitive. PJM is regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The MMU describes congestion:

Congestion is neither good nor bad, but is a direct measure of the extent to which there are multiple marginal generating units dispatched to serve load as a result of transmission constraints. Congestion occurs when available, least-cost energy cannot be delivered to all load because transmission facilities are not adequate to deliver that energy to one or more areas, and higher cost units in the constrained area(s) must be dispatched to meet the load. The result is that the price of energy in the constrained area(s) is higher than in the unconstrained area.

The MMU recommends the creation of a mechanism to permit a direct comparison, or competition, between transmission and generation alternatives, including which alternative is less costly and who bears the risks associated with each alternative.

Attempting to monkey with congestion is an attempt to levelize prices across a region. Should the same energy costs to customers near a coal-fired generator in Pennsylvania be available to customers in Washington, D.C., who closed all their dirty electricity generators years ago? Shouldn't there be a price to pay for that? If congestion relief lowers prices in Washington, D.C., then prices must rise elsewhere. Think of it as a teeter-totter. As prices fall somewhere, they must go up somewhere else. The MMU says:

For example, congestion across the AP South Interface means lower prices in western control zones and higher prices in eastern control zones. Load in western control zones will benefit from lower prices and receive a congestion credit (negative load congestion payment). Load in the eastern and southern control zones will incur a congestion charge (positive load congestion payment).

The MMU's annual State of the Market Report has a section devoted to congestion costs tracked over the year, as well as an analysis of current transmission planning.

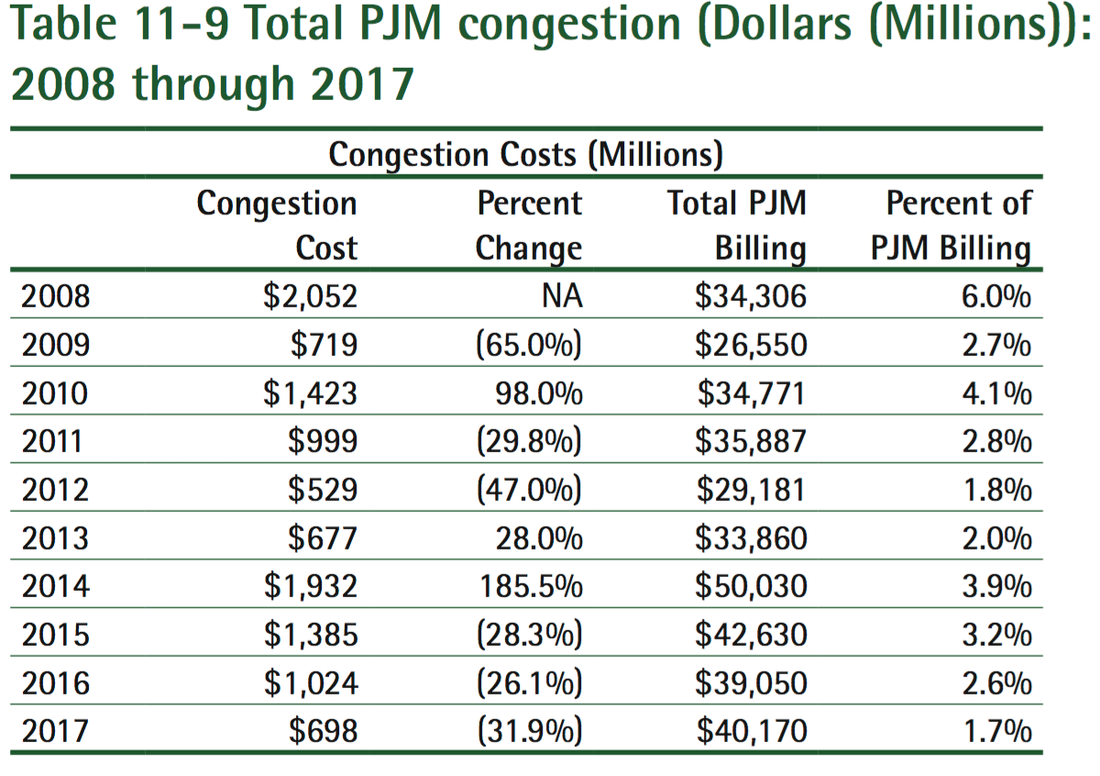

Let's take a look at the MMU's tracking of congestion costs over the past 10 years:

The AP South Interface was the largest contributor to congestion costs in 2014. With $486.8 million in total congestion costs, it accounted for 25.2 percent of the total PJM congestion costs in 2014.

Fast forward 4 years and the 2017 State of the Market reported

The Braidwood - East Frankfort Line was the largest contributor to congestion costs in 2017. With $43.4 million in total congestion costs, it accounted for 6.2 percent of the total PJM congestion costs in 2017.

Of course we don't. But the last one to realize this seems to be PJM. If PJM is so slow to react to changing energy markets, perhaps it shouldn't plan and order market efficiency projects that take more than 6 years to come to fruition. Perhaps it needs to adopt the MMU's long-standing recommendation to change the way it evaluates congestion fixes. Perhaps PJM is simply in love with its processes and has forgotten its mission to benefit consumers.

It's time to cancel the Transource Independence Energy Connection.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed